|

Camp at Swan Hill

Sep. 8. 1860.

To the Hon. Secretary

Royal Society

Dr J. Macadam M.L.A.

Sir,

Sunday, 19 August 1860.

I left Melbourne to take charge of the Camp in the Royal Park. Up all night up watching.

Monday, 20 August 1860.

All day engaged with packing and loading. Mounted a Camel at 4 p.m. and marched with the greater part of the Exploring Party past Moonee Ponds and camped near Essendon. One of our waggons broke down before reaching the halting-place; at sunset a horse of ours broke loose and ran away.

Tuesday, 21 August 1860.

Horse caught again this morning; the remainder of the waggons arrived; unloading and reloading the same. Started at 2¼ p.m. All the horses, the camels and six waggons went on together. A valuable little watch-dog belonging, to Mr Landells, was lost. We arrived at 6 oCl p.m. at a paddock near the Inverness hotel, Bulla.

Wednesday, 22 August 1860.

One of the Indians, Samla, begged of Mr Landells to discharge him; his religion (being a Hindu) would not allow him to eat meat, except mutton, and this only if the sheep was killed by himself The poor fellow looked very poorly indeed having had nothing for the last three days but bread and plenty of work. He saw it was impossible for him to remain with us without breaking his faith. After receiving the wages due to him he touched with his fingers mother Earth and then his forehead, and blessing Mr Landells and the men near him, this good man went his way towards Melbourne his eyes full of tears. We started at 10 a.m.; the appearance of the sky was not at all of a cheering character, before we reached Bolinda, near Captain Gardners place at 5 p.m. it commenced raining, and ere night had set in it came down in torrents. No tea, no fire; we slept in the wet.

Thursday, 23 August 1860.

Fine morning, but damp and cold. Marched at 10¼ a.m. Captain Gardner received us hospitably, refusing payment for hay and other things given to the party. The black soil, the result of decomposed basalt or lava-was in consequence of the heavy fall of rain, last night turned into a sort of mud, resembling black soft-soap, dangerous and difficult for a camels foot and a great hindrance to our waggons. It is a very tedious and tiring work to lead on foot a camel through such ground and at the same time taking good care that no branch over head or on the ground interfere with walking or rather skating. Notwithstanding this we arrived at Lancefield at 6 o' clock p.m. 17 miles distant from our last nights camping place.

Friday, 24 August 1860.

Again a wet night and blowing hard from the N.W. Struck our tents at ¼ to 9 a.m. and went on over a hilly ground, leaving the rich basaltic soil behind us. About a mile after quitting Lancefield a sandstone formation, N.W. of the township, offered a fair road for our poor beasts; soon after the sandstone we met with Granit, which again was exchanged for sandstone. After crossing the 'Big Hill' the ascent and descent of which caused some delay, we were most heartily received by a poor family living in a hut at the 'Accommodation Paddock' in front of which we awaited the arrival of our waggons. The housewife offering us tea and milk, which was gladly accepted, refused at the same time to take payment for it, however, her rosy cheeked children at the door of the hut differed from their mothers view and shaking hands with us strangers accepted a few shillings, which they were told by the good women to keep it as a 'memento cameli' which I think is the proper translation for a 'camel token' as she called it. On we went and by 4 o'C p.m., we pitched our tents in a paddock belonging to Dr Baynton, Darlington, 12 miles from Lancefield. At the Doctors place unfortunately there was no hay nor any other feed for the Animals, so we cut wattels down which were not refused by them. Scarcely had we arrived on the ground when we were saluted and hailed by a cloud, discharging a deluge followed by a shower of hail.

Saturday, 25 August 1860.

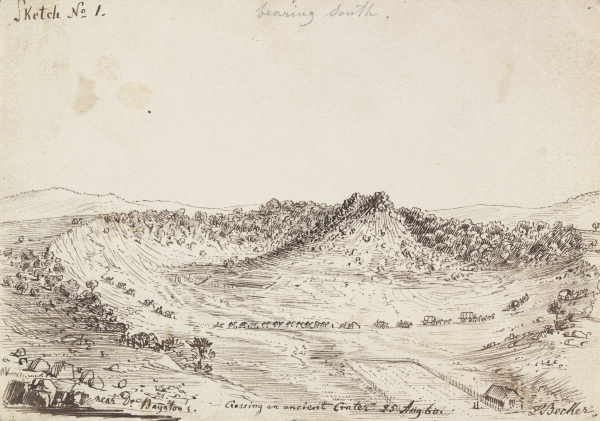

The morning was foggy and this prevented me at first to observe that our camp was near the edge of an ancient crater of about one half or three-quarters of a mile diameter, near the centre of which a cone rose, covered with blocks of basalt; the whole of the rim and the plaines beyond it belong to the same formation. The outlet of this crater is towards the North, through which at present a current of water runs with a marshy, rich soil on both sides. From this outlet I sketched the Sketch No 1.

It was with extreme difficulty to bring the Waggons and the Camels down and up again those steep sides of this crater, which we however accomplished without serious accident in about one hours and a half time. How far my view in regard to this being an ancient crater, be correct or not, Mr Taylor the Assistant Geological Surveyor will tell. I forgot to mention that we lost more than three-quarters of an hour after starting, through a butcher who run after us with a bill for £3.16 for some beef and chaff and as the bill was written with pencil on a minute piece of dirty paper without Dr Baynton's signature, we were obliged to wait till every thing was properly done; I could not help comparing the poor woman's conduct of yesterday with this day's, of course, right business like act. -The road was good after leaving the crater, passing at noon through a country with strong indications of being auriferous, intersected with basaltic formations which later formed the main feature of the Spring Plains over which we, in the afternoon, travelled with the utmost difficulty on account of the slippery ground and great number of crab-holes. Here some of our waggons were forced to remain all night having been bogged. These desolate plains end near the Mia-Mia public house. Before reaching that place a steep hill, composed of quartz, has to be descended, on the foot of which the basalt predominates again. Arrived at the Mia Mia at 5¼ p.m. Rain in the evening. A Camel bit one of the Indians through the finger. I forgot to mention that the three Indians remaining with the camels are Mohametans and not so particular about their food. They are willing, steady and good working fellows.

Sunday, 26 August 1860.

Hoar frost in the morning; fine weather. A day of rest. Finished Sketch No 1. Copied accounts, bills etc. for Mr Burke. A great many visitors are coming in from McIvor and other places to look at the caravan; the Landlord of the Inn had a good day and behaved well towards the Exploring party, his charges were very moderate.

Monday, 27 August 1860.

Marched at 9¼, via Wild Duck Creek to Matheson's. With some difficulty we got the Camels through the Creek, they never before went through water worth mentioning. The road being good and level, we once more mounted the Camels and arrived at Matheson's hotel at 4 o'C p.m. Distant 14 miles from the Mia Mia.

Tuesday, 28 August 1860.

Damp night, Mr Burke send to Bendigo for several things wanted. We left Matheson's at 8¾ a.m. and arrived at 1 p.m. at the Campaspe, which we crossed with a punt at Kennedy's. We camped near that place in a fine, well graced paddock, where already a number of friends from Bendigo and others, the curious loving, people were found awaiting the Caravan. Notwithstanding some Gentlemen of the Exploring party endeavoured to satisfy several of the inquisitive visitors and to answer their time robbing questions as correct as possible, it seems after all that the writer of an article in the Bendigo Advertiser very much misrepresented some of the facts as well as some of the men connected with the Exploring Expedition.

Wednesday, 29 August 1860.

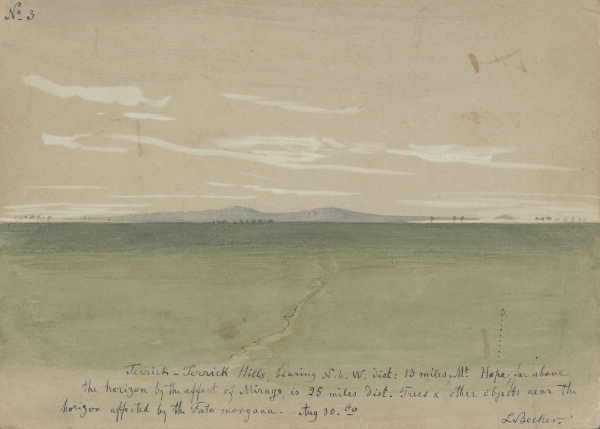

Clear, cold night. We received a few newspaper, where I read that my discovery of native Zink found a further confirmation. Our departure from the camp at 9¼. a.m. was witnessed by a number of gentlemen, cheering when we entered the bush, through which we steered towards Patersons, said to he 12 miles, but we found it to be 24. There is no certainty about the distances in the bush and plains, the travelers being almost all on horseback underate generally the distances when asked: how far is it from here to there? - After a few miles ride we found ourselves in the Terrick plains. The effect on one who sees extensive plaines for the first time is somewhat very peculiar: the plain looks like a calm ocean with green water; the horizon appears to he much higher than the point the spectator stands on, the whole plain looks concave. On you go, miles and miles, a single tree, a belt of timber appeared at the horizon, affected by the mirage; you reach that belt of small trees, a Wallaby, a Kangarooh-rat disturbs for a moment the monotony, and a few steps further on you are again on the green calm ocean. The sun was setting and our party, steering northwards, received the full effect of the golden rays of the sun; the contrast with the green plains was very striking. I could not help sketching the Scene which is very poorly represented in Sketch No 2. We arrived at Patersons station at 6 p.m. Even here, away from Bendigo, several vehicles from Sandhurst loaded with men and children arrived late in the evening to have a look at the Camels.

Thursday, 30 August 1860.

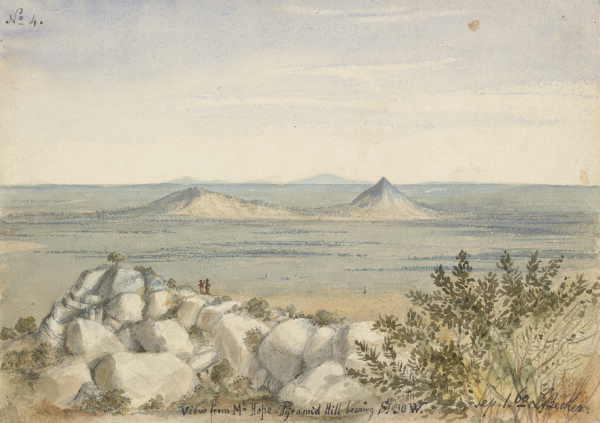

Cold, clear night. One of the visitors from Bendigo broke this morning his arm, he sought for help in our camp, when Dr Beckler set the bones and left the man more comfortable than the sufferer himself expected. Marched at 9 a.m. our course NbyW - When about 12 miles from the Terrick-Terrick Hills the effect of the Mirage brought the hills considerably above the horizon, both ends of the chain of hills floating in the air; the same was the case with Mount Hope, distant 25 miles, whose base was unconnected with the horizon; nearly all the objects near it floated in the air, they became however contracted and partly disappeared when approaching them. Sketch No 3 gives a correct outline of this scene. We arrived 4 p.m. at Dr Rowe's station on the foot of the Terricks.

Friday, 31 August 1860.

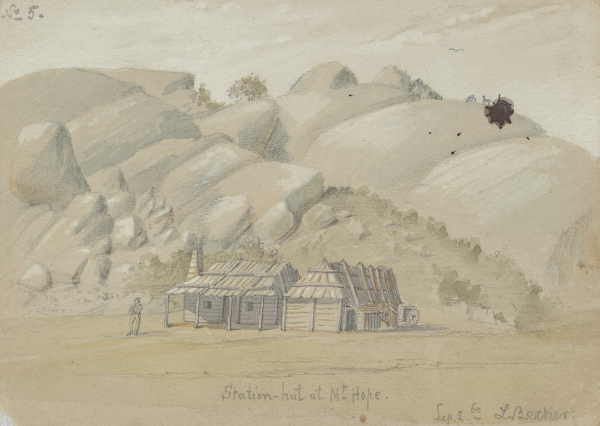

A day of rest and fine weather allowed me to finish Sketches 2 and 3 and to make some general observations. The Bendigo Creek, on whose banks the station is built, is here named Picanini Creek, and further to the North it is called Mount Hope Cr. The water is still a yellow coloured, floating mud, the effect of the washings at Bendigo. Dr Rowe dammed the water and by this process is enabled to support a greater number of sheep during the hot seasons, than it was possible before this damming system of the different waters in these plains was introduced. In the afternoon 4 natives, among them a lubra, went their Stepps slowly towards the camp. With eyes and mouths wide open, speechless they stared at the Bunjibs, our camels, but refused to go nearer than a spears-throw. Although no strangers at Dr Rowe's station, and notwithstanding our assurance that the camels were only harmless 'big sheep', they turned their back towards them and squatted soon round a far off camp fire of their own, conversing in their native tongue; probably about the character of these illustrious strangers. If this first interview between natives and camels might be used as a criterion when coming in contact with the blacks in the course of our future journeys, then, surely, we might spare the gunpowder as long as the mesmeric power of our Bunjlbs remain with them. The Terrick Hills are composed of a fine granit, not very hard, and a more compact, coarse one; both kinds are used by Dr Rowe for building purposes. The brick-walls of the houses are lined with them. The Terrick plains are free from any stone, and consist of a ferruginous loam and sometimes of clay intermixed with small bits of calcareous or limestone (?) concrete. During the dry season these plaines are bare of grass and hard like bricks, after a fall of rain they become muddy and soon after are covered with a fine verdure. We passed several skeletons of bullocks, said to have been killed by lightning, a common occurrence in these plains.

| |